Welcome back. In the first post, we set up a basic conversational agent. It worked. It responded. It was... fine.

But let's be honest - an agent that can only chat is just a very expensive echo chamber. Today we're giving our agent actual knowledge. It will remember past conversations, search through its own message history, and - most importantly - decide when to use that knowledge.

This is going to be a long one. Grab coffee. Let's build the next piece of the puzzle.

What We're Building

By the end of this post, we'll have:

- A PostgreSQL database for persisting messages and embeddings

- A second agent (KnowledgeSearch) that searches conversation history

- Tool calling so our main agent can invoke KnowledgeSearch when needed

- Autonomous decision-making about when to retrieve information vs. just respond

That last point is the key difference between classic RAG and agentic RAG. We're not blindly stuffing context into every prompt. The agent chooses when retrieval helps.

A Quick Word on RAG

RAG - Retrieval-Augmented Generation - has been the go-to pattern for giving LLMs access to external knowledge. The classic approach:

- User asks a question

- System searches a knowledge base

- Retrieved documents get stuffed into the prompt

- LLM generates a response using that context

It works. But it's also... dumb? Every query triggers retrieval, whether needed or not. Ask "What's the capital of France?" and you're still embedding the question, searching vectors, retrieving documents. Wasteful.

Agentic RAG flips this. The agent has tools for retrieval and decides when to use them. Simple questions get simple answers. Complex questions trigger the agent to go digging. Much more elegant.

Heads up: There's a whole universe of RAG variations out there - hybrid RAG combining vector search with full-text search (FTS), reranking strategies, query expansion, and more. If you go down the rabbit hole, you'll find dozens of ways to improve retrieval quality. We're intentionally skipping all of that here to focus on the agentic part - how an agent decides when and how to retrieve. Once you grok that, feel free to explore the retrieval optimizations.

Enough theory. Let's write some code.

Database Foundation

Our agent needs a place to store things - messages, embeddings, knowledge. PostgreSQL with pgvector gives us a solid foundation.

The Schema

We're keeping it simple: messages for chat history, embeddings for semantic search.

%%{init: {

"theme": "dark",

"themeVariables": {

"fontFamily": "Jetbrains Mono",

},

"themeCSS": [

".er.relationshipLine { stroke: #858585; }",

".er.relationshipLabel { fill: #bbbbbb; }",

".er.relationshipLabelBox { fill: transparent; }",

".er.entityBox { fill: #252526; stroke: #303031; }",

"[id^=entity-messages] .er.entityBox { fill: #1e3a5f; stroke: #5abae0; }",

"[id^=entity-embeddings] .er.entityBox { fill: #451a03; stroke: #f59e0b; }"

]

}}%%

erDiagram

messages ||--o| embeddings : "has"

messages {

uuid id PK

uuid conversation_id

uuid embedding_id FK

varchar role

varchar author_name

text content

bigint sequence_number

timestamp created_at

}

embeddings {

uuid id PK

varchar source_type

uuid source_id

text content

vector vector_1536

timestamp created_at

}

A few notes:

- conversation_id: Groups messages by conversation/session - indexed for fast retrieval

- role: Maps to

ChatRole.Valuefrom Microsoft.Extensions.AI (user,assistant,system,tool) - sequence_number: Auto-assigned by a database trigger - ensures correct ordering

- source_type: Polymorphic pattern - can reference

Messageor any future entity (e.g.,DocumentChunk) - vector_1536: 1536-dimension embedding from OpenAI's

text-embedding-3-small

The DbContext

Entity Framework Core handles the mapping. The key thing we need is pgvector support:

// KnowledgeDbContext.cs

modelBuilder.;

This single line enables the vector data type in PostgreSQL. Without it, EF Core won't know what to do with our embedding vectors.

For the Embedding entity, we tell EF Core the exact column type:

// KnowledgeDbContext.cs

entity.

.;

The rest is standard EF Core configuration - indexes on ConversationId (our primary query pattern), composite index on ConversationId + SequenceNumber for ordered retrieval, and SourceType + SourceId on embeddings for fast lookups.

Don't skip the indexes. Without them, you're doing full table scans.

Wiring It Up

Database registration goes into our extension method. The important choice: AddDbContextFactory instead of AddDbContext.

// ServiceCollectionExtensions.cs

services.;

Why the factory? Our message store and agents live outside the normal HTTP request lifecycle. The factory pattern lets each operation spin up its own short-lived context.

Migration Time

EF Core migrations version our schema:

# Create the migration

# Apply it

We also add a trigger migration for auto-incrementing sequence numbers:

// 20251224000001_AddCustomTriggers.cs

migrationBuilder.

RETURN NEW;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

""");

migrationBuilder.

""");

This assigns sequence numbers per conversation. The WHERE conversation_id = NEW.conversation_id ensures each conversation has its own sequence. For high-concurrency production use, consider using a proper sequence/identity instead of MAX().

The Conversation Workaround

Before we get to the message store, there's a wrinkle. The framework's DevUI doesn't pass AgentThread information to custom ChatMessageStore implementations. No thread ID means no way to group messages by conversation using the framework's intended abstractions.

We could give up on persistence entirely. Or we could be pragmatic.

The workaround is dead simple: generate a conversation ID once at startup.

// ConversationWorkaround.cs

public static

One GUID, initialized once when the application starts, shared for the lifetime of the process. Every message gets tagged with that ID. Restart the app? New ID, new conversation.

We add a corresponding ConversationId column to our Message entity - just a Guid property that gets persisted alongside the role, content, and sequence number.

The Message Store

With our workaround in place, the ChatMessageStore implementation becomes straightforward. The framework calls AddMessagesAsync after each exchange, and GetMessagesAsync when loading history.

The key insight: we use IDbContextFactory<KnowledgeDbContext> instead of injecting a DbContext directly. Why? The store lives outside the normal HTTP request lifecycle. The factory pattern lets each operation spin up its own short-lived context - no connection leaks, no stale entity tracking.

When adding messages, we tag each one with ConversationWorkaround.CurrentConversationId:

// KnowledgeChatMessageStore.cs

var message = ;

When retrieving, we filter by that same ID:

// KnowledgeChatMessageStore.cs

var messages = await dbContext.Messages

.

.

.;

This keeps each app instance isolated. Messages from yesterday's debugging session don't pollute today's conversation.

Why This Workaround?

The ideal solution would use the framework's AgentThread abstraction - each thread gets its own conversation, the UI manages thread creation, everything Just Works™. But DevUI doesn't pass thread information to custom stores yet.

Good news: our ChatMessageStore does get called. Messages persist. The agent loads context on startup. The workaround gives us:

- Per-instance conversations: Each app restart starts fresh

- Persistent context: Within a session, the agent remembers everything

- Future-proof schema: When DevUI supports threads, we swap

ConversationWorkaround.CurrentConversationIdfor the real thread ID

We've opened issue #3000 to track proper thread support. For now, this gets the job done.

Embeddings

Before we can build our KnowledgeSearch agent, we need to understand embeddings - the foundation of semantic search. If you already know this, skip ahead. If not, buckle up - this is genuinely cool. And surprisingly simple once you see it.

This section covers the theory, but we're not just hand-waving. As we go, we'll be building toward our second agent that can search through conversation history and return relevant context.

The Big Reveal

An embedding is just a list of numbers. That's it. That's the tweet.

%%{init: {"theme": "dark"}}%%

flowchart LR

A["🐱 cat"] --> B["[0.021, -0.034, 0.089, 0.012, ..., -0.045]"]

style A fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style B fill:#252526,stroke:#303031,color:#bbbbbb

When you feed text into an embedding model, it spits out a vector - 1536 floating-point numbers for OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small. These numbers encode the meaning of the text. Not the letters, not the spelling - the actual semantic content.

The magic? Similar meanings produce similar numbers.

%%{init: {"theme": "dark"}}%%

flowchart LR

A["🐱 cat"] --> V1["[0.021, -0.034, 0.089, ...]"]

B["🐈 kitten"] --> V2["[0.019, -0.031, 0.092, ...]"]

C["🗳️ democracy"] --> V3["[-0.067, 0.142, -0.023, ...]"]

style A fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style B fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style C fill:#451a03,stroke:#f59e0b,color:#fff

style V1 fill:#252526,stroke:#303031,color:#bbbbbb

style V2 fill:#252526,stroke:#303031,color:#bbbbbb

style V3 fill:#252526,stroke:#303031,color:#bbbbbb

See how "cat" and "kitten" have similar-ish numbers, while "democracy" is completely different? That's semantic similarity, encoded as math.

The "magic" demystified: This is the whole secret behind AI "understanding" - it's just numbers. There's no mystical intelligence, no consciousness pondering the nature of cats. Just insanely clever linear algebra operating in 1536-dimensional space. Once you see it, you can't unsee it. Beautiful, really.

Where Things Live in Vector Space

Here's where it gets fun. Imagine plotting these vectors in space (we'll pretend it's 3D because humans can't visualize 1536 dimensions - and if you can, please contact DARPA immediately). Instead of an interactive Three.js canvas, let's keep it simple with a mermaid sketch that still shows clusters and similarity scores.

%%{init: {

"theme": "dark"

}}%%

flowchart LR

subgraph Pets[" "]

A[cat]

B[kitten]

end

subgraph Civics[" "]

D[democracy]

E[parliament]

end

A ---|"0.94"| B

A -.-|"0.31"| D

D ---|"0.89"| E

style A fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style B fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style D fill:#451a03,stroke:#f59e0b,color:#fff

style E fill:#451a03,stroke:#f59e0b,color:#fff

Similar concepts cluster together. Words about pets huddle in one corner, political terms in another. In the real 1536-dimensional space, these relationships become incredibly nuanced - the model captures categories, analogies, context, even vibes. The scores on the edges are cosine similarities: higher numbers mean those meanings live closer together.

This is why semantic search works. Ask "how do I create an agent?" and the system finds documents about "instantiating agents" and "agent initialization" - different words, same neighborhood in vector space.

How "Close" Are Two Vectors?

We use cosine similarity - basically measuring the angle between two arrows in space.

- Similarity = 1: Identical meaning (same direction)

- Similarity = 0: Unrelated (perpendicular)

- Similarity = -1: Opposite meaning (opposite direction)

You don't need to understand the math. Just know: higher number = more similar meaning. When we search our knowledge base, we're finding the vectors that point in roughly the same direction as the query.

%%{init: {"theme": "dark"}}%%

flowchart LR

subgraph Query

Q["How do I build an agent?"]

end

subgraph Results["Top Matches (by similarity)"]

R1["0.94 - Creating your first agent"]

R2["0.91 - Agent initialization guide"]

R3["0.87 - Setting up agent tools"]

R4["0.34 - PostgreSQL connection strings"]

end

Q --> R1

Q --> R2

Q --> R3

Q -.-> R4

style Q fill:#1e3a5f,stroke:#5abae0,color:#fff

style R1 fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style R2 fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style R3 fill:#064e3b,stroke:#10b981,color:#fff

style R4 fill:#451a03,stroke:#f59e0b,color:#fff

The PostgreSQL doc isn't wrong, it's just pointing in a completely different direction. Low similarity score, doesn't make the cut.

The Model We'll Use

OpenAI offers several embedding models:

| Model | Dimensions | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

text-embedding-3-small | 1536 | Most applications |

text-embedding-3-large | 3072 | When you need more context |

text-embedding-ada-002 | 1536 | Legacy |

We'll use text-embedding-3-small. It's cheap, fast, and good enough for most use cases. The larger model is more accurate but costs more - classic tradeoff. Start small, upgrade if you need to.

Now the question becomes: where do we store 1536 floating-point numbers per piece of text, and how do we search them efficiently?

pgvector Setup

PostgreSQL with pgvector gives us a proper vector database without leaving our existing stack. No separate Pinecone or Weaviate instance to manage.

Enabling the Extension

First, we need pgvector enabled in our database. Connect to PostgreSQL and run:

CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS vector;

This installs the vector data type and operators. You only need to do this once per database. If you're using my dev container template, this is already handled in the database initialization scripts.

Verify it worked:

SELECT * FROM pg_extension WHERE extname = 'vector';

-- Should return one row showing the vector extension

The Embedding Entity

We want a generic approach - store embeddings for any content type (messages, documents, whatever). The key property:

// Embedding.cs

public Vector Vector = null!; // pgvector's native type

We use pgvector's native Vector type instead of float[]. The Pgvector.EntityFrameworkCore package handles the mapping between C# and PostgreSQL.

The entity also tracks what was embedded via SourceType + SourceId - a poor man's polymorphic association. Not elegant, but flexible. We can add new source types (documents, code snippets) without schema changes.

We also store the original Content alongside the vector. Why? When we retrieve matches, we need the actual text to show. And if embeddings get stale, we can re-generate from the stored content.

EF Core Configuration

We already covered the key line in Section 1 - HasColumnType("vector(1536)"). The dimension must match your embedding model. OpenAI's text-embedding-3-small produces 1536 dimensions, so that's what we use.

Indexing for Speed

Without an index, similarity search scans every row - fine for 1,000 embeddings, catastrophic for 1,000,000. HNSW (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) gives us logarithmic search time.

We create the index via a migration (we include this in our AddCustomTriggers migration):

// 20251224000001_AddCustomTriggers.cs

migrationBuilder.

""");

Breaking this down:

hnsw: The index algorithm - builds a graph structure for fast nearest neighbor searchvector_cosine_ops: Use cosine distance (1 - cosine similarity) as the metric- Creation time: ~1-2 seconds per 10,000 vectors on my laptop

The tradeoff: HNSW uses more memory and takes longer to build, but queries are dramatically faster. For a RAG system, this is always worth it.

Embedding Messages

Time to give our agent some actual knowledge. Instead of indexing external documentation, we're embedding our own conversation history - every message becomes searchable.

Why Messages?

We need something to embed, and chat messages are already there - no external datasets, no document ingestion pipelines, no extra setup. It's demo content that generates itself as you use the agent.

Important distinction: This is not the same as

Microsoft.Agents.AI.Memory.ChatHistoryMemoryProvider, which provides memorable context during agent invocation (think: short-term working memory for the current conversation). What we're building is long-term semantic search over historical content. Different problems, different solutions.

The Chunking Problem (Or Not)

For large documents, chunking is essential - split into smaller pieces, embed each one. But messages are already bite-sized. A typical chat message is well under our embedding model's context limit.

We'll embed messages as-is. No chunking needed. If you later want to add document indexing (PDFs, markdown files, whatever), you'd apply chunking:

- Fixed size: Every chunk is N tokens. Simple but might split mid-sentence.

- Paragraph-based: Split on natural boundaries. Preserves context but uneven sizes.

- Semantic: Use the LLM to identify logical sections. Expensive but smart.

For documents, fixed size with overlap (500 tokens, 50 token overlap) is the standard. But for messages, we skip this entirely.

The Embedding Service

We wrap IEmbeddingGenerator<string, Embedding<float>> from Microsoft.Extensions.AI in a simple service. The key conversion:

// EmbeddingService.cs

var result = await _embeddingGenerator.;

return ;

Text goes in, pgvector Vector comes out. The service handles the conversion from the AI library's float array to pgvector's native type. Nothing fancy - just a thin wrapper to keep the embedding generation consistent across the app.

Background Processing

We could embed messages synchronously when they're saved, but that blocks the chat response. Instead, a background service picks up unprocessed messages every 10 seconds.

The trick is using Message.EmbeddingId as both a foreign key and a processing flag:

// EmbeddingBackgroundService.cs

var pendingMessages = await dbContext.Messages

. // Not yet embedded

.

.

.

.;

For each message, we generate the embedding and link it back. Once EmbeddingId is set, that message won't be picked up again.

No chunking, no complexity. Message goes in, vector comes out, gets stored. The SourceType = "Message" links back to the original - we'll use this when searching.

The KnowledgeSearch Agent

With embeddings being generated in the background, we need a way to search them. Enter the KnowledgeSearch agent - a specialized agent for semantic search over conversation history.

Why an Agent Instead of a Simple Tool?

You could just wire up a tool function. But wrapping it in an agent brings benefits:

- Clear separation: Search logic lives in its own class, testable in isolation

- Dependency injection: Proper lifetime management for database contexts and services

- Composability: Later, we can add more specialized agents (DocSearch, WebSearch, etc.)

This is the "agentic" part of agentic RAG - agents with tools, each specialized for their task.

The Implementation

The flow is straightforward: embed the query, search pgvector, format results.

First, we embed the search query using the same model that embedded our messages:

// KnowledgeSearchAgent.cs

var queryVector = await _embeddingService.;

Then the vector search - this is where pgvector shines:

// KnowledgeSearchAgent.cs

var results = await dbContext.Embeddings

.

.

. // DefaultMinScore = 0.40

.

. // DefaultTopK = 10

.;

A few notes:

CosineDistance()returns distance (0 = identical, 2 = opposite), not similarity. Lower is better.- Threshold of

(1 - 0.40)means we want at least 40% similarity. TweakDefaultMinScorebased on your use case. IDbContextFactorygives us a fresh context per search - the agent is a singleton, but each query gets its own connection.

Finally, we fetch the actual messages and format them with timestamps. The timestamps matter - they help the LLM understand recency.

The pgvector Query

Under the hood, EF Core translates our LINQ to:

SELECT e.*, e.vector <=> @queryVector AS distance

FROM embeddings e

WHERE e.source_type = 'Message'

AND e.vector <=> @queryVector <= 0.6 -- 1 - DefaultMinScore

ORDER BY e.vector <=> @queryVector

LIMIT 10;

The <=> operator is pgvector's cosine distance. Lower distance = better match. The HNSW index we created earlier makes this logarithmic instead of linear - critical at scale.

Wiring It Up

Now we connect everything in AgentFactory and Program.cs.

The Agent Factory

Wiring the tool is the key step. We use AIFunctionFactory.Create() to turn our instance method into something the agent can call:

// AgentFactory.cs

var searchAgent = services.;

return chatClient.;

The [Description] attributes on our method and parameters become the tool's schema - the LLM sees them and knows what the tool does and what arguments it needs.

ToolMode = ChatToolMode.Auto is important. It tells the model to decide when to use tools, rather than always using them or never using them.

The system prompt is equally crucial. We tell the LLM when to use the tool:

DECISION FRAMEWORK:

- For general knowledge (math, common facts): Answer directly without tools

- For recall questions ('did we discuss X?'): Use SearchConversationHistory

- When unsure if something was discussed: Search first rather than guessing

Without this guidance, models either never use tools or use them for everything. The prompt teaches restraint.

Registration in Program.cs

The key registration:

// Program.cs

builder.Services.;

Why singleton? The agent factory resolves from the root provider during startup. This is safe because KnowledgeSearchAgent only depends on singletons (IEmbeddingService, ILogger) and factories (IDbContextFactory) - no scoped services leaking through.

The rest follows the same pattern we established: AddAIAgent with factory delegates, AddHostedService for the background embedding processor.

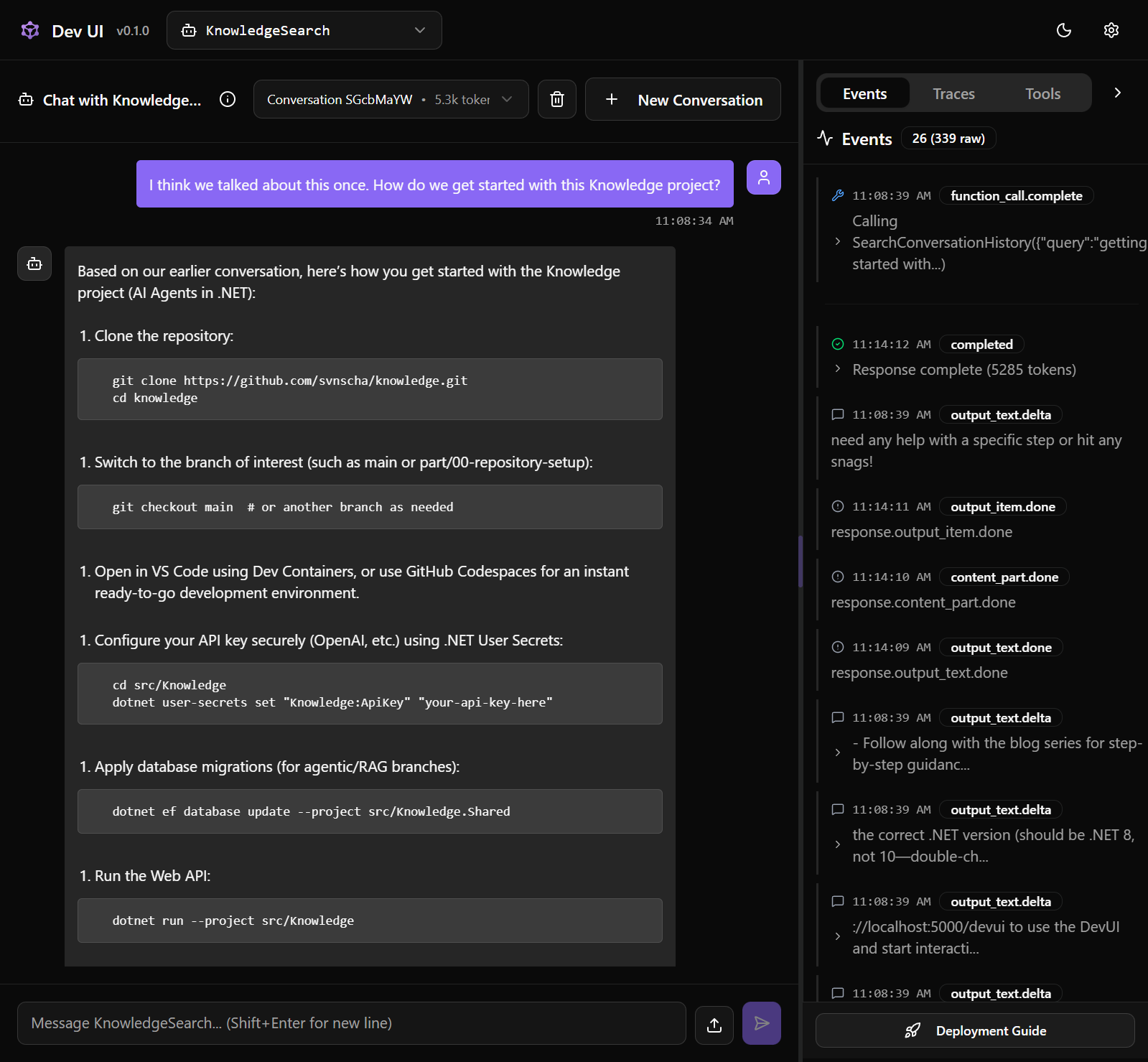

Before and After

Let's see the difference:

Without RAG:

User: "What did we discuss about database indexes?" Agent: "I don't have memory of our past conversations..."

With KnowledgeSearch:

User: "What did we discuss about database indexes?" Agent: calls SearchConversationHistory("database indexes") Agent: "Based on our earlier conversation, we discussed adding indexes for ConversationId and the composite index for ordered retrieval..."

Night and day.

Wrapping Up

We've covered a lot of ground today, but we're still just scratching the surface.

We learned how to take abstract concepts like embeddings and store them in an actual database using pgvector. We saw how to consume that knowledge by building a specialized agent that can perform semantic searches over our own conversation history.

Along the way, we touched on the importance of database persistence, the nuances of tool calling with AIFunctionFactory, and how to manage agent lifetimes in a .NET application. We also explored chunking and more advanced RAG strategies like hybrid search and reranking - topics that are definitely worth exploring as you dive deeper into the world of AI.

The full code is on the part/01-agentic-rag branch. Clone it, run it, break it, and most importantly, make it your own.

I highly recommend checking out Microsoft's official examples. Some features, like search, are implemented differently in the framework itself because it provides higher-level abstractions (like TextSearchProvider). While those abstractions are useful, I wanted to show you what's happening under the hood.

Here are some examples worth checking in the Microsoft Agent Framework repository:

Agent_Step03_UsingFunctionTools/Program.csAgent_Step06_PersistedConversations/Program.csAgent_Step07_3rdPartyThreadStorage/Program.csAgent_Step12_AsFunctionTool/Program.csAgentWithRAG/*

What's Next?

We've built something useful today - an agent that doesn't just talk, but remembers. But this is really just the beginning of the journey.

The next logical step is moving beyond simple retrieval and into the world of the Agent Loop. Instead of a single "ask and receive" interaction, we'll look at how agents can enter a cycle of reasoning, acting, and observing. This is where the real magic happens: the agent tries a task, observes the result, and adjusts its strategy until the job is done. It's the foundation of building autonomous coding assistants that can actually work alongside you.

As these agents become more autonomous, we also need to know exactly what they're thinking. That's why we'll be diving into Observability and tracing so we can peek inside the "black box" and see every tool call, every reasoning step, and every decision the agent makes in real-time.

We're moving from "chatbots" to "collaborators." I'll see you in the next one as we start closing the loop. 🚀